El Gobierno alemán, encabezado porAngela Merkel, sitúa España como el nuevo problema de Europa, según informa el medio americano Bloomberg, que cita fuentes de la cancillería. Además de ser el peor Estado en combatir el coronavirus, no tiene gobierno estable desde el 2015 y tiene dos problemas irresueltos: el conflicto de Catalunya y la decadencia de la monarquía, recuerda.

Según Bloomberg, a Merkel le preocupa tanto el hecho de que España, y en concreto Madrid, se hayan convertido en el foco de la pandemia del coronavirus en la UE, como el hecho de que se está revelando en el país una “política tóxica”. La crítica se suma a la que ayer sábado hacía The Economist desde el Reino Unido, que hablaba de una “política venenosa”. “Las autoridades alemanas observan la situación de España con una preocupación creciente”, explica. Añade sin ambages que “el sistema político español está roto”, una imagen pésima porque entra en la vía que finaliza en el Estado fallido.

“España está pagando un precio alto por su sistema político roto y se está convirtiendo de forma acelerada en el niño problemático del euro. Antes normalmente era Italia la que se veía como el riesgo mayor. Pero ahora las autoridades de Alemania, que es el motor económico de la UE y quien paga más dinero en el fondo de recuperación de la Covid, están preocupadas por lo mal que España está afrontando la pandemia”, indica.

En el fondo está el caos político que atenaza la capital española. “El rebrote de los contagios desde finales de verano ha puesto al descubierto viciosas divisiones partidistas en España, con autoridades de la administración regional de centroderecha en Madrid que desafían con acritud las nuevas restricciones que ha impuesto el Gobierno socialista estatal. Y el resultado ha sido una espiral en la crisis sanitaria”, indica.

Según Bloomberg, hasta ahora Alemana y los Estados del Norte se habían hecho los despistados con España porque la economía tiraba bien, pero ahora eso cambiará y aplicarán más rigor. “Durante años, las autoridades del resto de Europa han hecho la vista gorda a la aspereza y a las disfunciones de España, mientras la economía iba funcionando. Pero cuando la cuarta economía del euro se ha hundido en la peor recesión económica de Europa, se ven obligados a seguirlo más de cerca”, avisa.

Añade que en el Gobierno de Berlín ha empezado a preocupar que España pueda provocar un efecto domino negativo en otros Estados de la UE, “incluida Alemania”.

Según el gran medio económico americano, además de los temas habituales que la mayoría de Estados tienen que abordar -como equilibrar las demandas de empresas, trabajadores, jóvenes y jubilados- “España se enfrenta a dos cuestiones fundamentales que el establishment se niega a encarar: qué hacer con la monarquía y qué hacer con Catalunya”, dice. “España es vulnerable”, concluye, y recuerda que ha tenido 4 elecciones en cinco años y funciona con un presupuesto prorrogado desde el 2018.

Spain’s Toxic Politics, Health Woes Have Got Merkel Worried

Spain is paying a hefty price for its broken political system and is rapidly becoming the euro’s problem child.

It used to be Italy that was seen as the bigger risk. But now officials in Germany, the region’s economic motor and the one paying the most money toward the European Union’s Covid-19 recovery fund, are worried by just how badly Spain is coping with the pandemic.

The resurgence in infections since the end of the summer has exposed the country’s vicious partisan divisions, with officials from the center-right regional administration in Madrid bitterly challenging new restrictions imposed by the Socialist national leadership. The result is a spiraling health crisis.

“It’s a political war and politicians are campaigning instead of acting united against the pandemic,” said Manuel de Castro, a doctor at Madrid’s 12 de Octubre hospital and a union leader. “We’re lacking leadership and a clear chain of command.”

For years, officials in the rest of Europe have been able to turn a blind eye to the acrimony and dysfunction in Spain as the economy kept humming along. But after the euro’s fourth-biggest economy plunged into Europe’s worst recession yet, they are being forced to take a closer look.

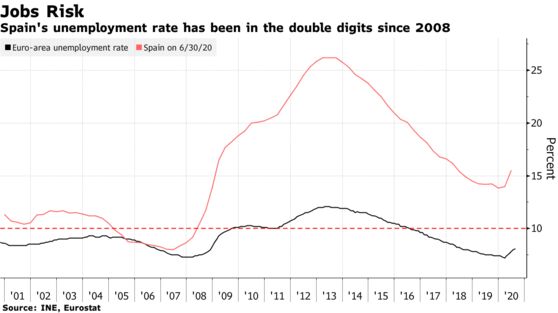

Spain’s economic slump will far deeper than the euro-area average

According to a person familiar with discussions within the government in Berlin, there’s real concern about a knock-on effect on member states, including Germany.

Spain has not had a stable government since 2015. But there was a degree of complacency about its ability to cope given that the economy had been barreling along on autopilot thanks to robust consumer spending and record tourist numbers.

Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez was complacent too this summer when he declared a premature victory over the virus. Since then, politicians have been trying to score points and avoid the blame for new curbs on daily life as the infection rate spiraled.

That has turned the Spanish capital into a new global virus hotspot. Spain has suffered a contraction in the second quarter of almost 18%, and the situation could get a lot worse if the authorities don’t swiftly get a grip on the situation.

Meanwhile, the economic costs are mounting.

The International Monetary Fund warned that Spain’s revival is under threat and that risks are “tilted strongly to the downside.” The Spanish central bank forecasts the economy could shrink as much as 12.6% this year.

EU leaders moved quickly to try to help hard-hit countries such as Spain bounce back, approving a landmark 750 billion-euro ($879 billion) recovery package. But ongoing disagreements risk delaying disbursement of the funds.

On top of the usual questions that most countries have to tackle — how to balance the demands of businesses and workers, young people and retirees — Spain is facing two fundamental questions that the establishment is reluctant to confront: what to do about the monarchy and Catalonia.

Opposition to the royal family has been fueled by the decade-long fall from grace of former king Juan Carlos, but opening that constitutional sore point could invite another debate on a referendum on Catalan independence.

Spain is vulnerable. The bitter aftermath of the financial crisis has already demolished the old two-party system which ensured a smooth alternation of power between left and right for 35 years after the return of democracy.

And the divisions have impeded the formation of a new consensus on how Spain should be run, leaving a series of weak, minority administrations. Bickering among Spanish authorities has undermined efforts to curb Covid-19 from spreading, according to 85% of people polled by GAD3 for ABC newspaper.

The nation has had four governments in five years and is currently operating on a budget rolled over from 2018 that was written by the previous conservative government. Millions of Madrid residents are now living with tough restrictions on daily life that took effect after a showdown between Sanchez and the leader of the Madrid region.

Isabel Diaz Ayuso, a conservative, initially threatened not to implement the restrictions. “We’re the only country in the world where the government only blames the capital city,” Ayuso said Thursday. “In other countries, presidents roll up their sleeves and work with their administrations, they don’t blame whoever is below them.”

When the pandemic struck in March, Sanchez decreed a state of emergency, which allowed his government to wrest powers from regional administrations. As the virus ebbed, he allowed them to manage the reopening of their economies but as students returned to school, the number of infections rose, especially in Madrid.

Sanchez asked Ayuso to get the virus under control. She, in turn, accused his left-leaning national government of singling out her region because it’s run by the main conservative opposition group, the People’s Party. That left Health Minister Salvador Illa imploring everyone that “we must listen to the science” and that “this is not an ideological battle.”

Ayuso’s management of the pandemic has been controversial from the start. In May, she became infected herself and self-isolated in a luxury penthouse apartment in Madrid. The region’s head of public health resigned because she disagreed with Ayuso’s crisis management.

Meanwhile, medical professionals say there aren’t enough contact tracers, doctors and nurses.

“We’ve been squeezed like lemons,” said Paloma Tamame, an ambulance doctor in Madrid. “There’s a point when you run out of patience, of tolerance, of resilience.”