Credit card companies are tracking shoppers like never before. In the battle between data brokers and privacy advocates, the latest front is the credit card.

On Privacy.com, shrouding your online shopping habits sounds easy: Enter your debit or bank account information, and the website generates a virtual debit card. This so-called burner card acts as a buyer by proxy, keeping your name and billing address out of view. Simply type its number, expiration date, and CVV code into any e-commerce site, hit purchase, and Privacy takes over. The service charges your actual card, adds those funds to the burner one, and uses the new card to do the actual shopping.

The promise is appealing. The card can be configured so that retailers can’t tack on any additional charges, such as an automatic subscription fee. If the retailer’s site gets hacked, you just ditch the burner and move on. And if anyone involved in the transaction tries to sell your data, the only card information they’ll have is that the purchase came from Privacy.

This isn’t the only service offering to mask people’s transactions. Last August, Apple introduced the Apple Card, a Goldman Sachs–issued, no-number credit card that won’t track your purchases. Privacy and other upstart software companies such as FigLeaf and Abine are working on burner cards and other technologies, such as password managers and browser extensions that cloak your web surfing. Offline, consumers have always been able to buy things anonymously with cash. But online, it’s a different story. “We want to give consumers the control to say, ‘I love doing business with you, I want to participate on the internet—I just want to do it on my terms,’ ” says Abine cofounder Rob Shavell.

We’ve become accustomed to the grim fact that nearly every major advertiser, website, and personal device maker collects and monitors users’ data to some extent. Some do it for their own purposes. Others do it in the service of various algorithmic spymasters, such as Facebook or Google, which analyze vast arrays of personal information—from social media likes to GPS locations—to serve up relevant ads. (Fast Company, like many other media outlets, tracks reader data for advertising purposes.)

The reality is far more complicated. In one sense, cardholders are safer from identity theft than ever before. At the same time, they’re now shopping in a panopticon, with companies tracking and analyzing their purchases in near real-time. It’s never been tougher to know who’s out there watching and selling this data—to say nothing of who’s buying.

Companies have been tapping into transaction data to sell us more things as early as the 1990s, when credit card giants such as American Express analyzed purchases to tailor special offers to cardholders. Marketers with more limited vantage points, meanwhile, pooled the data from their own cash registers to get a better view of their customers.

The landscape changed dramatically when fintech startups came knocking a decade later. Banks were at first wary of sharing data and working with them, largely because of the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which mandates penalties on financial institutions that put customer data, including names, birthdays, addresses, and other personal identifiable information, at risk. To solve this, the startups implemented a sophisticated system that erases personal details and replaces them with randomly generated pseudonyms that act like ID codes: They are unintelligible on their own, but can later be matched up with individual customer files.

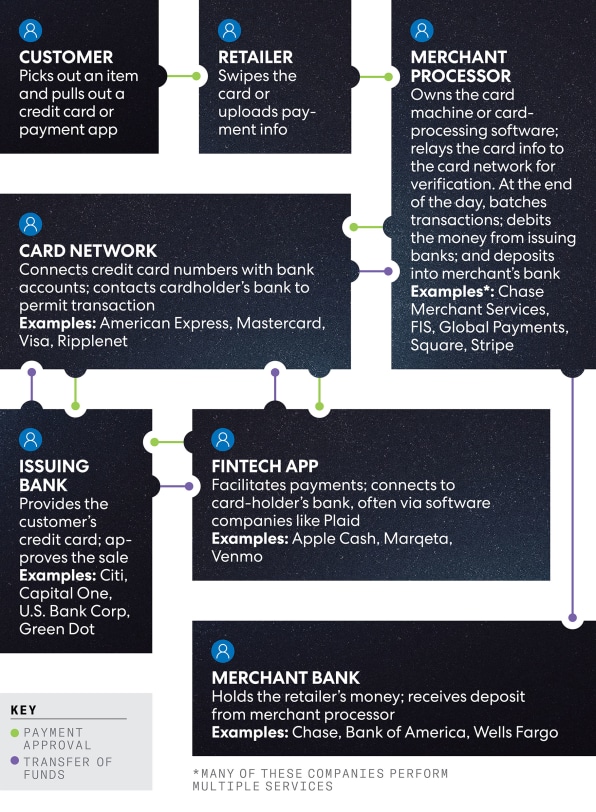

This substitution system (also known as tokenization) is now standard. Chip cards, contactless payment systems such as Apple Pay, online payment methods, and other internet banking technologies rely on it to connect with one another. They even form daisy chains: If an e-commerce app needs to accept credit cards, it uses software provided by a payment processor like Stripe. If a financial services app such as Acorns wants to link to customers’ bank accounts, it can use an API from Plaid, which automates logins. If a wealth-management app wants to give users a dashboard view of their credit card, savings, and investment accounts, it can use software from a company called Yodlee.

Today, any American who has bought something online has almost certainly had their data passed along by their card company and middleware startups. And some of those middlemen profit from what they see by selling information to marketers, hedge funds, and other brokers.

Tokenization “effectively created a loophole,” says Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, who heads the computational privacy group at Imperial College London, and who has advised the European Commission on privacy issues. By removing names and other details, companies can argue “that it’s not personal data; it’s ‘anonymized,’ ” he says.

But it isn’t so anonymous. In 2015, de Montjoye and colleagues at MIT took a data set containing three months’ worth of credit card transactions by 1.1 million unnamed people and found that 90% of the time, they could identify an individual if they knew the rough details (the day and the shop) of four of that person’s purchases. In other words, a combination of a few receipts, tweets, and Instagram photos of your dining out is enough to reveal your other purchases.

All of this is happening under a veil of secrecy. Credit card companies may acknowledge that they make money from analyzing transactions, but they are vague about what data they actually share. Visa, for example, says its data business only provides transaction histories on an aggregated zip-code level. But the zip codes it uses are zip+4 numbers—specific enough to pinpoint the addresses on one side of one block of one street, and often a single address. (Visa says it shares this data in batches of cards to avoid revealing individual information.) American Express says it never sells transaction data to third parties. However, it does work with a data broker, called Wiland, to identify individual consumers whose purchasing habits match criteria supplied by marketers. (According to American Express, its “modeling methodology” protects cardholders’ privacy.) Targeting individuals based on transaction data is “ridiculously easy,” says Robert Brill, founder of Brill Media, which uses data from Mastercard and other sources to buy digital advertising on behalf of clients.

And then there are the fintech intermediaries. Plaid, which accesses bank account information on behalf of more than 2,600 apps, says it never sells user data. But, in January, the company agreed to be acquired by Visa, which sells data through a business called Visa Advertising Solutions. (Visa declined to comment on its plans for Plaid.) The financial-guidance app HelloWallet says it doesn’t sell data about unique users. But to access users’ accounts, it relies on Yodlee, which sells this information.

The government’s ability to police this trade is limited. In January, Senators Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Ron Wyden of Oregon, and Representative Anne Eshoo, of California, sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission demanding an investigation into Yodlee’s parent company, Envestnet, for selling customers’ data without their knowledge. Yodlee, for its part, claims it follows all applicable laws. “Congress needs to establish clear rules governing the corporations digging into our private lives,” says Brown. A bill introduced last October by Wyden, for example, would force companies to be more transparent about how they share consumer data. However, there’s no indication that the Senate will consider it anytime soon.

In the absence of regulation, apps such as Privacy and Abine have emerged to help consumers. But they still have ties to the data ecosystem. Privacy relies on Plaid. Abine uses Stripe, which won’t disclose the names of all its banking partners. (Plenty of banks share transaction data.) Even Apple, which prohibits Goldman Sachs from using its card data for marketing purposes, couldn’t get the same concessions out of Mastercard, its card network.

For a privacy-minded shopper, these services can certainly muddy the waters. But even they can’t fully extricate themselves from the swamp.